Seven Things You’re Forgetting with Your Back Squat

By Eric Bach

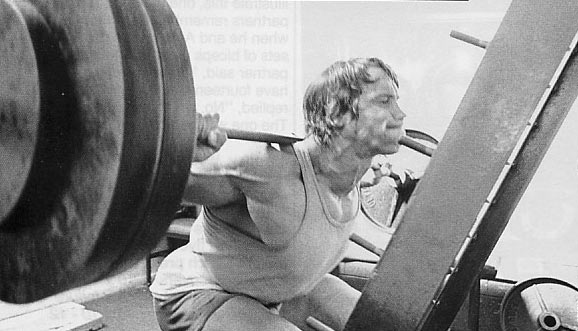

Squats are lifting loyalty for curing chicken leg syndrome’ and building high-performance muscle mass. Squats develop total body strength, stimulate tons of total body muscle growth, and improve athleticism. Yep, the squat reigns king among bang-for-your buck exercises.

Problem is, most lifters have the mobility of a caste iron skillet and lack ability to execute the squat safely and effectively.

This poses a huge problem—If you don’t squat safely and effectively a powerful tool becomes limited at best, dangerous at worst. To maximize the squat you need mobility to reach proper position and the stability to control movement through the intended range of motion.

Know this: without the form and technique you’ll still be squatting baby weights and have toothpicks for legs.

It’s time to maximize your squat potential through improving technique, mobility, and execution to take your high-performance training to another level.

Rack at the correct height:

We’ve all seen it: A rack set-up too high, a calf-raise walkout followed by the poor sap missing the rack and crashing to his knees during the set. This is non-sense and an idiotic way to get injured.

Set the rack up with the barbell set between nipple and shoulder height, low enough to allow you to squat to weight out and easily re-rack the weight when you’re fatigued. Make your mark and write down the “notch” in your workout log.

Shorten your walkout:

Your walkout needs to be the same each and every time. Get tight, feet even in the rack, squat the bar out; right back, left back, feet even.

That’s it—practice and rehearse every time you get under the bar. I see too many athletes take 7 steps every time they squat, wasting time perfecting their tap-dance rather than preparing for a battle. Taking too long in your walkout and set-up leads to overthinking and self-psyching out of your squat. Get underneath, get even, and get it done.

Bend the Bar:

Rather than being lazy with the bar get your Hulk on and bend the bar until the ends touch the ground. If you’re not actively applying force to the bar the bar will act on you—jumping and burying you in the rack.Drive your elbows down and back to engage the lats, providing a larger shelf for the barbell and additionally stability in the trunk. Solomonow, et al concluded that over 200 muscles are activated during squat performance, using them all will improve your performance.

Additionally, you’ll prevent the bar from jumping off your back during explosive squats, improving rep quality and decreasing injury risk. Plus, you won’t be that chump who loses a barbell behind your back during explosive squat work.

Spread the Floor:

Allowing the knees to buckle in, known as valgus collapse, is a great way to reinforce poor mechanics and set yourself up for a significant knee injury. Prevent valgus collapse by spreading the floor and pushing the knees out during the squat. This emphasizes hip and posterior chain development and skyrocketing your squat numbers.

Vary your stance:

Everyone has unique anatomical consideration that dictate which squat position is best for their body-type.

Don’t take any squat pattern as a must, especially if it’s painful.

Don’t take any squat pattern as a must, especially if it’s painful.

Got it? Good

Vary your squat among different positions to minimize weak-points and avoid overuse injuries. Get strong from multiple positions, not just your shortest range of motion.

Brace the core…Hard:

Imagine bracing yourself for a punch in the gut by Mike Tyson—That’s the tension and intent necessary for maximum core activation, strength, and safety.

Abdominal bracing involves contracting your abdominal musculature and low back muscles and bracing, like you were about to get hit lit up by Iron Mike. This produces a rigid, stable core for increased abdominal pressure, which according to myamota et al and Vakos et al creates greater spinal stabilization and a greater anti-flexion moment during dynamic lifts to decrease injury risk and improve performance.

Train the pause:

If you’re squatting to depth you need to be stable in the bottom position. Train the pause use submaximal loads and squat to maximum depth while maintaining trunk integrity—this means no butt-wink. Unless you’re training for a big total and need to hit certain depth the risk reward probably isn’t worth a rock bottom (bro-science translation: ass-to-grass) squat under load in the presence of butt-wink.

Squat Depth Considerations:

A parallel or sub-parallel squat is ideal when core integrity is maintained, but it rarely happens. In most cases greater depth is reached through “butt-wink,” resulting in the sacrifice of lumbar integrity and a greater risk of injury.

So what is it?

Butt-wink occurs when the butt “tucks” underneath the pelvis to reach greater depth and hip flexion. As a result, there’s a ton of additional stres on the lumbar spine.

Squatting with neutral spine (left) Vs butt-wink (right) photo-credit Bret Contreras

Squatting to depth with but-wink is hammering a square peg into a round hole and significantly increases the risk of injury. In most of my experiences butt-wink is the result of poor anterior core engagement, anterior core instability, and shortened hamstring length—the anterior core can’t counteract pulls from the hamstrings and adductor magnus and the forces on the pelvis, resulting in posterior pelvic tilt.

If you have a significant tuck best to hammer away at core stability work and squat only to positions when spinal alignment is maintained—even if it’s above parallel.

Squat Width Considerations:

A wider squat is used to increase loading and decrease range of motion. This is fantastic for powerlifters, but athletes need more specific considerations for foot placement for maximal transfer to on-field performance. Bodybuilders will benefit from a variety of stances to maximize muscle recruitment and minimize leg development imbalances. The cool part about squat stance width is different positions recruit different muscles.

A wider squat emphasizes:

McCaw et al reported a wide stance significantly increased activity of the gluteus maximus and adductor longus, with greatest activity seen at 140% shoulder width. If you’re looking for greater involvement of the glutes, hamstrings, adductors, and a shorter range of motion then a wide squat is worth a shot.

A narrow squat emphasizes:

A narrower stance keeps the hips closed and limits the involvement of the adductors and hammers away at the squats.

It’s imperative to consider anatomical differences with each athlete—a 6’6” basketball player is going to squat differently than 5’6” powerlifter.

Hip socket anatomy is unique to each individual, with some individuals having greater success deep squatting with a narrow stance and others succeeding with extremely wide stances. No amount of soft tissue work will increase mobility if there is a “bony block” creating restrictions and pain. I’ve had clients with seemingly great soft-tissue qualities try to squat wide only to find pain and vice-versa. The point is everyone won’t be able to squat the same--attempting to force it fights against your anatomy, leading to pain and dysfunction.

Whether it’s wide or narrow whichever squat position you maintain without pain or losing lumbo-pelvic integrity is your best bet.

Feet Flared OR Feet Neutral:

Either foot position is fine and is often dictated by squat stance. Most lifters who squat narrow keep the feet pointed neutral whereas wide stance squatters use a foot flare and to help “spread the floor,” prevent knee valgus, and further incorporate the hips. Excessive foot flare rotates the tibia and potentially causes issues with patellar tracking and varus/valgus movements.

I’ve found most individuals prefer a slight flare (15 degrees or so) of the feet, but your anatomy, goals, and comfort are the ultimate deciding factors. You’ll have to tinker with both positions and see what’s best for you.

Wrap Up:

Regardless of your goal the squat will help you succeed and is an integral part of successful high performance training programs.

Double-check the following during your next session:

- Shorten your walkout

- Rack at the correct height

- Bend the bar

- Shorten your walkout

- Spread the floor

- Vary your stance

- Train the pause

The squat is a technical movement and squatting for your body-type and goals is imperative to long-term success under the bar. Optimize your technique first, and then start piling on plates. Take these into consideration and you’ll be squatting big weights without pain for years to come.

Resources:

McCaw, ST and Melrose, DR. Stance width and bar load effects on leg muscle activity during the parallel squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31: 428-436, 1999.

McGill, S, Norman, RW, and Sharatt, MT. The effect of an abdominal belt on trunk muscle activity and intra- abdominal pressure during squat lifts. Ergonomics 33: 147-160, 1990.

Miyamoto, K, Iinuma, N, Maeda, M, Wada, E, and Shimizu, K. Effects of abdominal belts on intra-abdominal pressure, intra-muscular pressure in the erector spinae muscles and myoelectrical activities of trunk muscles. Clin Biomech 14: 79-87, 1999.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (). Squatting Kinematics and Kinetics and Their Application to Exercise Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24, 3497-3506.

Solomonow, M, Baratta, R, Zhou, BH, Shoji, H, Bose, W, Beck, C, and D'Ambrosia, R. The synergistic action of the anterior cruciate ligament and thigh muscles in maintaining joint stability. Am J Sports Med 15: 207-213, 198

Triplett, N. T., McBride, J., Blow, D., Kirby, T., & Dayne, A. (). Relationship Between Maximal Squat Strength And Five, Ten, And Forty Yard Sprint Times. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23, 1633-1636.

Vakos, JP, Nitz, AJ, Threlkeld, AJ, Shapiro, R, and Horn, T. Electromyographic activity of selected trunk and hip muscles during a squat lift. Effect of varying the lumbar posture. Spine 19: 687-695, 1994

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eric Bach, CSCS, PN1 is a strength coach, author, and fitness consultant. An avid fitness junky, Eric has been featured in publications such as T-Nation, eliteFTS, and thePTDC. He is owner of Bach Performance where he coaches clients to take control of their lives, helping them become stronger, shredded, and more athletic. Eric is the author of 101 Tips to Jacked and Shredded, which is available FREE for a limited time.

Website: http://bachperformance.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/bachperformance

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Eric_Bach

101 Tips to Jacked and Shredded: http://bit.ly/101-Tips-to-Jacked-and-Shredded